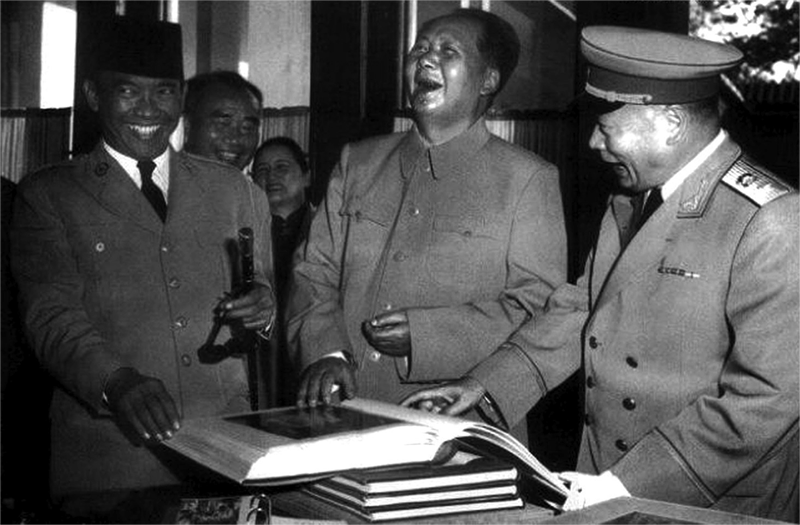

From Bandung to Berlin is an open and shared immaterial platform of collaboration that revolves around the interplay of historical locations and times between the first Afro-Asian conference in Bandung in 1955 and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The project begins from Bandung Conference because the meeting is considered as the birthplace of the so-called Third World and the non-aligned movement amidst the ideological battle between the Western and Eastern blocs. Meanwhile, the fall of the Berlin Wall is chosen to represent the symbolic coda to Cold War epoch that resulted with the collapse of communism and the triumph of capitalism, at least within the prevailing Euro-American horizon. The past is revisited in order to inspect the fragility of ideologies that emerged from Bandung 1955

and Berlin 1989: the so-called neutral ideology in

the former, and the so-called democratic capitalism in the latter.

By creating imaginative and indirect interconnections between these events, the collaborative project serves as a shared immaterial platform to invent new passages in history. In this project, the spatiotemporal distance from Bandung to Berlin is retraced with transnational approach through creating various speculative routes and networks that involve the fictionalization of history as its modus operandi. Deploying fiction as a necessary narrative mode, the project circulates within a precarious field of literature as a means to provoke a productive ambiguity that confronts the general ambiguous interplay of subjectivities between fictional and historical writings.