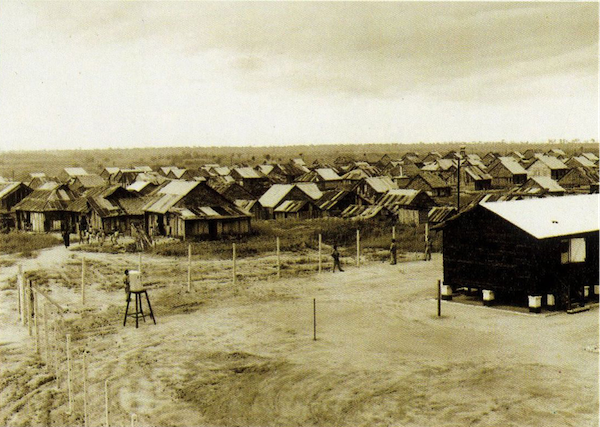

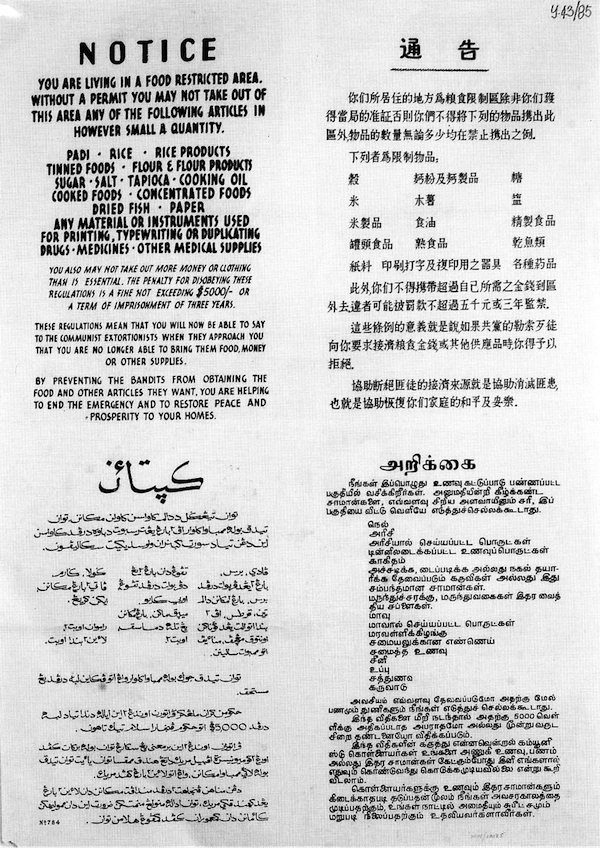

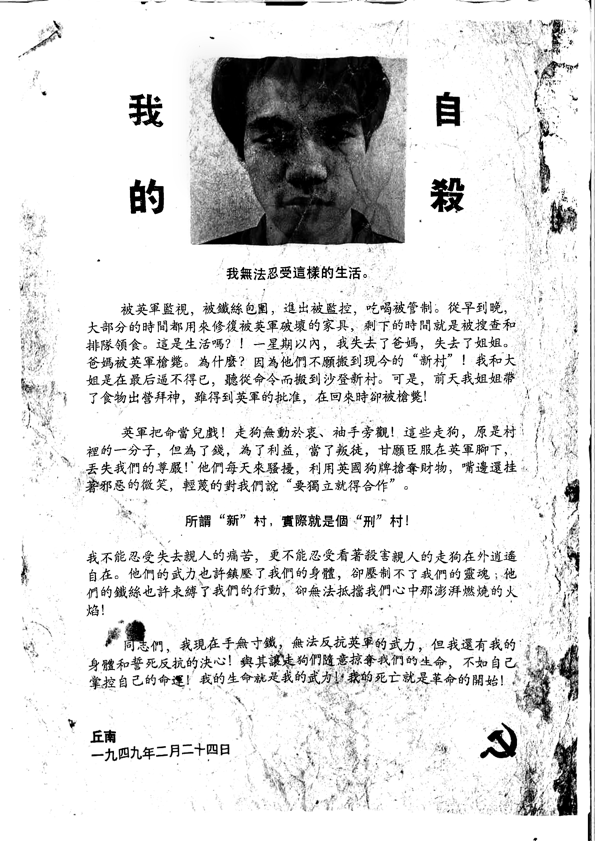

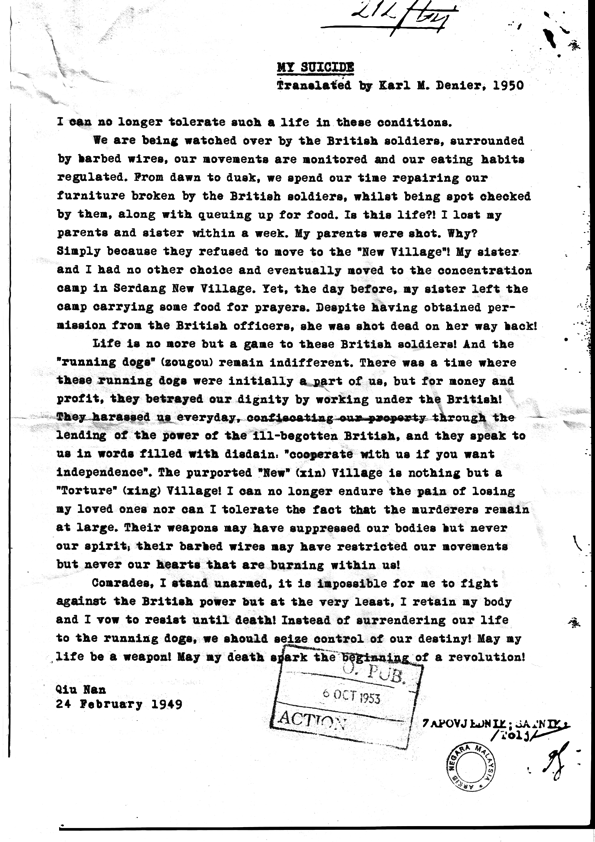

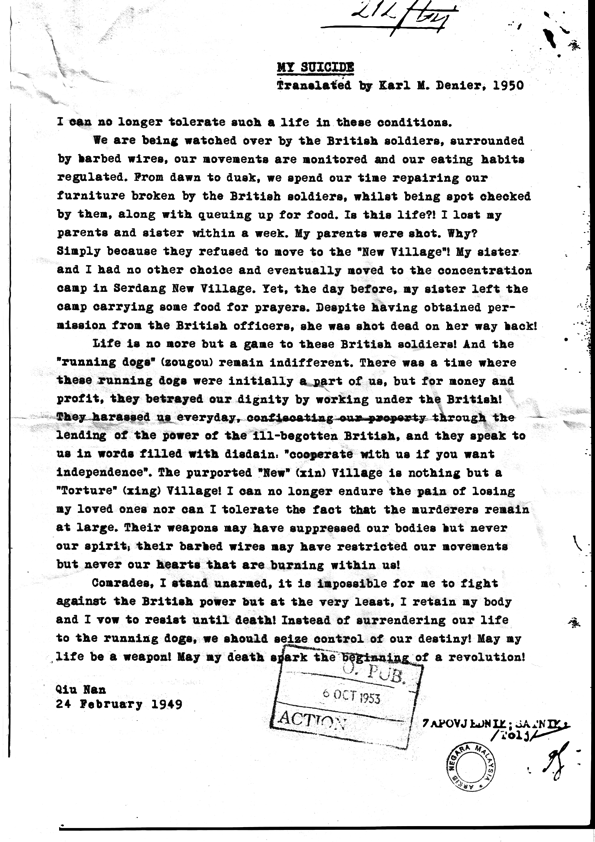

Just recently, a 15 years-old Chinese boy lives in the New Village, Malaysia, found a used milk bottle contained with a few rolled papers. The boy, who was going to plant papaya seeds in his backyard apparently had discovered a collection of Qiu Nan’s poems and a piece of paper, which seems to be ripped out from a poetry book written by Mao Zedong.

THE PEOPLE'S LIBERATION ARMY CAPTURES NANKING

April 1949

Mao Zedong

Over Chungshan swept a storm, headlong,

Our mighty army, a million strong, has crossed the Great River.

The City, a tiger crouching, a dragon curling, outshines its ancient glories;

In heroic triumph heaven and earth have been overturned.

With power and to spare we must pursue the tottering foe

And not ape Hsiang Yu the conqueror seeking idle fame.

Were Nature sentient, she too would pass from youth to age,

But Man's world is mutable, seas become mulberry fields.

THE MALAYAN COMMUNIST PARTY TAKES BANGSAR

September 1946

Qiu Nan

The rain will not stop on Bangsar,

For a hundred tigers stalk the jungle.

Their maws are red with victory, hackles

Raised towards the sky. The trees and rivers

Will run free outside of what the white man

Has the cheek to consider his burden. If the Crown governor

Wants some savages, they shall be served some savages. Let the jungles,

Plantations, potholes, caves, fields open their dark jaws and spit

out the furious sound of freedom—we may yet be wet behind the ears

but our hearts are ready to hold the weight of independence in our hands.

THREE SPARROWS: AN ELEGY

January 1949

Qiu Nan

The rice cakes are on the ledge

Waiting seven days and nights till

The sparrows return to their attap roost.

The dead return in a week to bid the

Living farewell, but killing three birds

With a single stone sorely misses the mark

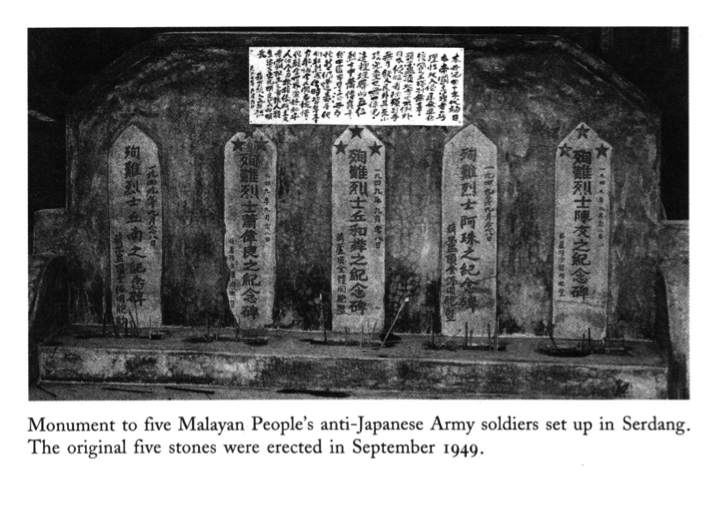

For am I not left standing in Serdang

A scarlet target between my wet eyes left

Out to dry on a clothesline in the New Village—

There is nothing new about the village because

Imperialism is old hat, so call a spade

A spade a sickel a sickel a sparrow a

dead sparrow that has soared to such great heights it

unshackles its feet from the wretched cage, trills

a song of injustice and sorrow as I weep

over the fresh soil dug up for my sister’s grave

alongside the wings of our parents, so too fodder for the worms.

TWO BIRDS: A DIALOGUE

Autumn 1965

Mao Zedong

The roc wings fanwise,

Soaring ninety thousand li

And rousing a raging cyclone.

The blue sky on his back, he looks down

To survey Man's world with its towns and cities.

Gunfire licks the heavens,

Shells pit the earth.

A sparrow in his bush is scared stiff..

"This is one hell of a mess!

O I want to flit and fly away."

"Where, may I ask?"

The sparrow replies,

"To a jewelled palace in elfland's hills.

Don't you know a triple pact was signed

Under the bright autumn moon two years ago?

There'll be plenty to eat,

Potatoes piping hot,

Beef-filled goulash."

"Stop your windy nonsense!

Look, the world is being turned upside down."

WINTER CLOUDS

December 26, 1962

Mao Zedong

Winter clouds snow-laden, cotton fluff flying,

None or few the unfallen flowers.

Chill waves sweep through steep skies,

Yet earth's gentle breath grows warm.

Only heroes can quell tigers and leopards

And wild bears never daunt the brave.

Plum blossoms welcome the whirling snow;

Small wonder flies freeze and perish.

EQUATORIAL STORMS

February 21, 1949

Qiu Nan

This too shall pass. For the glorious red banners

over our town’s archways have been sullied

down to a threadbare rag imperialists may stamp upon

to clean the loosened soil of our motherland off their boots.

Fertility too becomes fallow. I am only one man

made mortal, an equatorial storm to be played

on a lute in the winter of my discontent, a diseased

sore on a polio-ridden leg crying out for righteous

amputation, the final expiration hissing through my

teeth a toad’s croak for the necessity of revolution, heard

only by evanescent puddles already returning to the sun.